What has happened to China’s Economy and what should International Businesses Expect in the Coming Years

China’s post-pandemic recovery has been slower than most pundits originally expected. As a result, the following questions emerge for foreign firms doing business in the country:

- Is China’s economic growth and potential for international business investment permanently impaired?

- What is China’s leadership strategy for the economy?

- What will China’s economic trajectory be in 2024 and beyond?

- What opportunities remain for international companies and what risks should be mitigated?

China’s latest economic indicators and the experience of companies on the ground provide essential insights for the new strategies that international firms need to do business in the country.

Why is China’s Economy Slowing Down?

A number of events that took place during the COVID-19 years have permanently changed China’s economic outlook. Although they occurred in the second half of 2020, they were not caused by the pandemic itself or the growing geopolitical tensions of 2022 that together played only aggravating roles.

Still, the events that unfolded in the three pandemic years (2020-2022) have set China on a trajectory that might be difficult to reverse.

The Real Estate Crisis

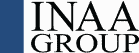

The crisis started with a decision by the central government to burst the real estate bubble. In August 2020, new regulations imposed limits on how much money real estate developers could borrow according to their financial situation. This triggered the much talked about defaults and bankruptcies of many of China’s real estate giants. Although apartment prices were carefully controlled by local government to avoid a crash in the market and a big fall in real estate prices, the value of the homes owned by the population dropped steadily. This trend became perceptible in the second quarter of 2023 and the decreases have accelerated in 2024.

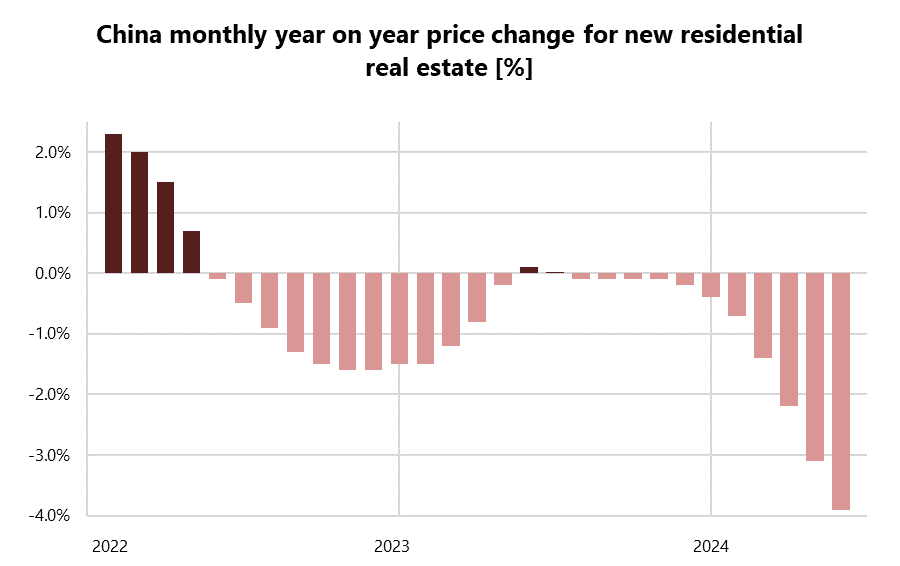

This crisis was unavoidable because the real estate industry was clearly in a bubble and government action needed. Even in 2018, 88% of all new urban homes were bought by families that already had a property, and over 90% of Chinese families owned their dwelling (Rogoff & Yang, 2020). However, these social accomplishments point to the end of growth in a key economic sector.

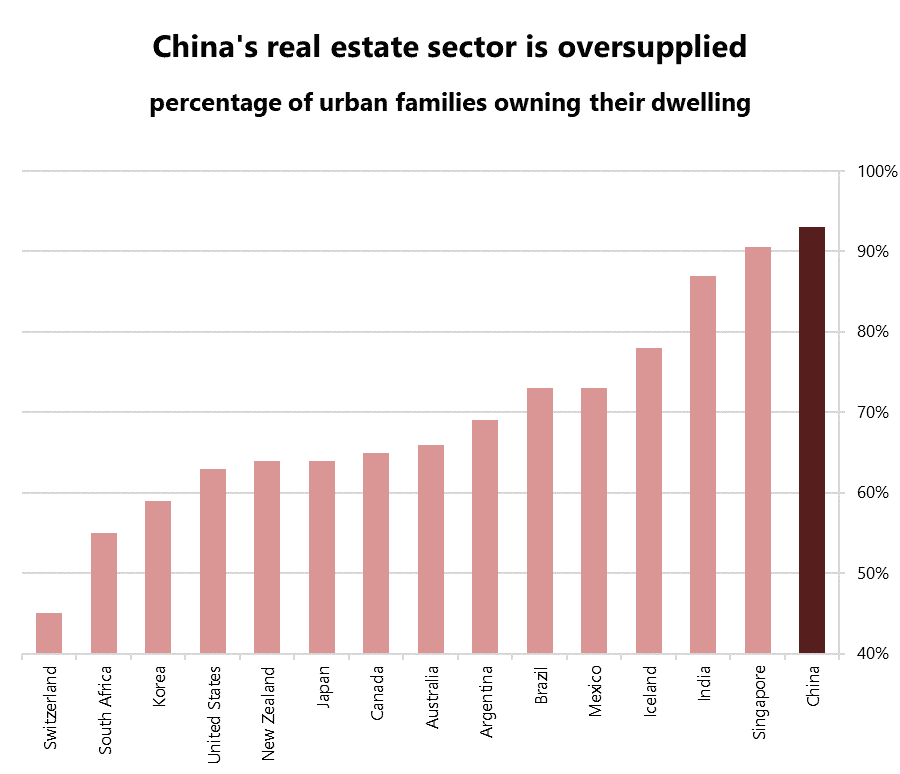

In addition, China’s total population started to shrink in 2022, a decline that has since accelerated. With fewer inhabitants, most of whom now own their homes, there is little need for more new housing in China. The result has been a steady drop in new construction projects that will eventually leave the real estate sector to work solely on the replacement and refurbishment of old homes.

China’s real estate sector and its dependent industries (for example, home decoration or household appliances) were at one point deemed to account for 25% or more of the Chinese economy (Rogoff & Yang, 2020). The sharp drop in this important sector’s activity has obviously resulted in lost jobs and business opportunities that have negatively impacted growth.

However, the fall in house prices has also reduced the wealth of Chinese consumers. Indeed, estimates indicate that about 70% of Chinese citizen’s wealth has been concentrated in real estate (Dong, 2020). With house prices declining even faster than new homes in the second-hand market, the Chinese middle class has seen its main store of wealth shrink.

This crisis in the real estate sector and its impact on how Chinese families perceive their falling wealth levels has been compounded by a second factor: the doldrums in the stock market.

Reining in the Big Private Tech Companies

In November 2020, shortly after the regulations to restrict funding to real estate developers, the Chinese government halted the IPO of the Ant Group a week before it was due to take place. (The Ant Group was the Alibaba company providing direct financial services to the users of the Alibaba group of internet companies.) In the same month, the Chinese authorities summoned 27 major internet companies to a meeting and instructed them to end their monopolistic practices, unfair competition, and counterfeiting (Zhang, 2023).

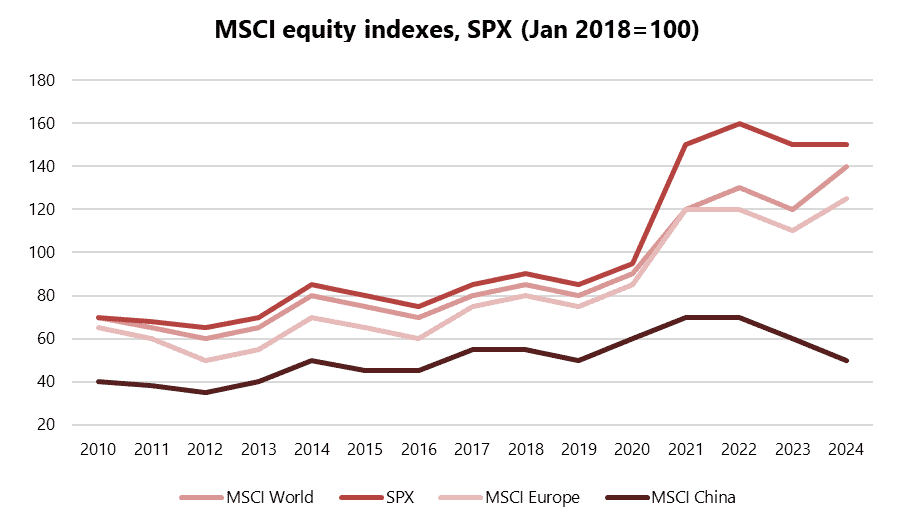

Fines were imposed on a number of companies and this drive to control the practices of the big tech companies, while probably needed, had a very negative impact on China’s stock market. It lost over 50% of its value in the 22 months from its peak on the 1st of January 2021 until the end of October 2022. After a mild recovery, the index was back down to the October level by the end of June 2024. (this has made the Chinese stock market the worst performing market in all major economies over the same period.)

A significant number of Chinese households have invested in the stock market and bought financial products that are linked to equities. On average, real estate property and stocks account for more than 80% of a Chinese individuals wealth.

Seeing their wealth steadily decline, Chinese families have taken a prudent and traditional path: they have saved and reduced their consumption. This has further reduced China’s growth potential and put additional pressure on the job market, already weakened by the employment lost with the end of the real estate boom.

As a result of this slower growth and tougher job market the feeling of economic insecurity in the population has been compounded (see Section 2.2 of this survey: retaining employees has become easier over the past 2 years).

Supply Chain Disruptions and the De-risking of Foreign Firms

China controlled the pandemic by locking down Wuhan, closing its borders, and applying a zero tolerance policy to the virus. This allowed China to become the supplier to the world in the second half of 2020 and 2021 at the time when the pandemic disrupted the rest of the world’s industrial production capacity. But in April 2022, the much more contagious Omicron variant of the virus started to spread, forcing a two-month lockdown of Shanghai. Due to the importance of the port city and the Yangtze Delta region, this lockdown caused significant disruption to international supply chains. It also made many international companies and nations aware of their dependency on China’s production capabilities.

At the same time, geopolitical tensions were steadily increasing. In August, 2022, three months after the end of the lockdown, China reacted strongly to Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan (at the time, she was third in line to the US Presidency). Coming after Russia’s unprecedented and unexpected attack on Ukraine in February, 2022 and the immediate sanctions that ensued, the risk of conflict in Asia suddenly became a key element in most international companies’ strategic considerations. It was no longer a far-fetched notion that trade restrictions could be imposed on China, just as they had been on Russia.

In the 40 years since China’s opening to foreign business and development, international firms only had to consider Chinese and global economics to define their strategies. In the space of a few months, they now unexpectedly needed to consider their Chinese supply chain risks.

Needless to say, the possible re-election of a protectionist US President who has promised to be impose 60% tariffs on all Chinese good entering the US has kept this risk very alive in the minds of business leaders, as is highlighted by the McKinsey June 2024 global survey of CEOs (McKinsey & Company, 2024). As a consequence, before the end of 2022, international companies started shifting their supply chains out of China. The suppliers of these multinationals have been the first to feel the impact of this new de-risking atmosphere (Business Insider, 2023).

A well-known example of de-risking is Foxconn, the major contract manufacturer for Apple products based in Taiwan. It has been the biggest private employer in China since 2011, providing 1 million Chinese jobs and, until 2020, manufacturing practically all of Apple’s products in China. However, in fiscal year 2023 (Capoot, 2024), Foxconn produced 14% of the world’s iPhones in India, twice the amount that were made there in fiscal year 2022.

The companies that are transferring production out of China still rely to a great extent on components made there. However, when suppliers set-up production sites out of China they also look for lower cost locations. It is therefore quite likely that these components will also be localized in Thailand, Vietnam, India, Mexico, or other new manufacturing destinations, as happened in China when it became the manufacturing country of choice.

International trade is an important part of China’s economy: it accounts for about 20% of China’s employment (Zhang & Woo, 2022), probably more than the real estate industry does today. Keeping in mind that China-based foreign companies were responsible for 31.5% of Chinese exports and 35% of its imports in 2022 (Textor, 2024), both international trade and foreign direct investment are critically important to China’s economy. It is then not surprising that the Chinese government is putting enormous efforts into rebuilding its global economic relations.

China’s Economic Policies and Responses to Maintain High Growth Rates

The Chinese consumer confidence trap

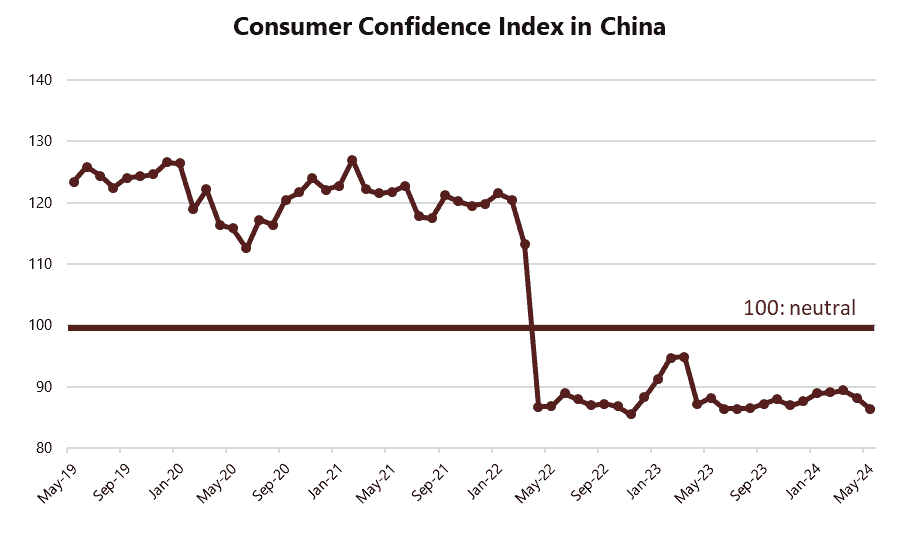

The Third Plenum of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China started on 15 July 2024, but did not strongly address the decreasing spending enthusiasm of Chinese consumers, though confidence is unprecedentedly low. Since April 2022, the confidence index (published officially by the National Bureau of Statistics) has been at a historically low level of around 86, with the exception of the rebound that happened in early 2023 when China cancelled all pandemic control measures. Previously, the lowest the index has been since first being recorded in 1990 is 97 (a score of 100 indicates neutral consumer confidence).

Instead of encouraging domestic consumption, the Chinese leadership has elected to promote innovation and technology development to generate more added value and achieve further growth.

The Promotion of Investments to maintain Growth Causes Overcapacity and Trade Tensions

Chinese consumers are definitely spending more frugally than in the pre-pandemic years. Domestic retail sales growth for the first 6 months of 2024 reached only 3.7%, about half what it was in prior to the pandemic. However, this does not mean that the Chinese do not have money. In fact, the situation is quite the contrary: households saved during the pandemic as consumers did in other regions of the world, but in China, this trend has continued post-pandemic.

In fact, the Chinese have even increased their savings rates. They are now saving more than 35% of their incomes. In comparison, Germans, save slightly more than 10% and Americans just about 3%. The result of such a savings pot is an uncontrolled investment boom in sectors that are seen as very promising, such as electric vehicles, battery manufacturing and other green technologies.

To take the example of electric vehicles, at the time of writing there were over 100 manufacturers of EVs in China, down from 500 active companies in 2019! (Bloomberg News, 2023). The unsurprising consequence of this rush to promote EV manufacturing is a severe underutilization of Chinese automotive manufacturing capacity, 35% of which was idle in the first quarter of 2024 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2024).

The solar panel industry is another case in point. China’s expected production capacity in 2024 is 900 GW (Clean Energy Associates, 2024). At the same time, global demand is expected to reach only around 400 GW (SolarPower Europe, 2023). In other words, China has the capacity to produce more than double the total quantity of solar panels that the world will need in 2024.

This overcapacity has predictably been spilling over China’s borders and is one of the reasons for the protectionist reactions now being touted by other countries. The US has led the way by imposing (among others) 100% import taxes on Chinese EVs. The EU is following (albeit with lower proposed tariffs and subject to ongoing negotiations with China to see if an agreement can be reached).

However, the protectionist reaction is not limited to developed economies. On 2nd July 2024, Indonesia announced up to 200% tariffs on certain low-cost Chinese imports (Strangio, 2024). Brazil has imposed quotas on a number of steel products and is also ramping up import duties on EVs that will reach 35% (Reuters, 2024).

China’s Investment-driven Growth Model is Leading to Slower Growth

Underconsumption means Overinvestment

China’s high levels of savings are leading to high levels of investment as a result of Chinese households’ low level of consumption. Consumption as a percentage of GDP is now much lower in China than it has been for any other economy at a similar stage of development. Now that the real estate sector is no longer able to absorb China’s high savings rates, manufacturing is seeing overinvestment.

In such a situation, economists calculate that without reforms to transfer sufficient income to households to boost consumption in China, the country’s growth must eventually go down to 2-3% per year until its economy is rebalanced, i.e., investments and consumption are in a proportion that fits China’s stage of economic development (Pettis, 2022). The problem is that no other country in a situation similar to China has previously managed such transfers because they go against vested interests (in China’s case, mostly local governments and the businesses that work for them).

If one country in history is capable of carrying out such transfers, it is certainly modern China with its huge state capacity. Still, at this moment in time, no decision to transfer wealth to households (either through higher wages or more generous social security) has clearly been made, though a growing number of Chinese economists clearly recognize the need to do so.

Based on this Macro View, what should we Expect in Practice?

China’s leadership is accustomed to achieving what it sets out to do. It is therefore likely that Chinese leaders will use all their resources and experience to continue achieving relatively high growth rates (4.5-5%) in the years to come, try to avoid the erection of trade barriers against Chinese products, and continue to increase their exports to the world.

We should expect that this strategy will succeed, at least in many markets and for some time to come. In fact, exports from China grew by 3.8% in the first 6 months of 2024 when compared to the same period in 2023, and the June 2024 trade balance hit a monthly record of USD 99 billion. indicating that consumers are buying fewer imported products (which amounts to import substitution).

However, we should also also expect that, over the next few years, protectionist measures will be put in place by both major economies, as well as some less-developed ones to reduce China’s export potential.

As a result, the already brutal competition within the Chinese market will only intensify and continue to bring producer prices down (China’s Producer Price Index has been in negative territory since September 2022). Very low inflation is also likely to continue to prevail (China’s inflation was 0.2% in 2023 and 0.1% in the first half of 2024). With low inflation and a reduction of interest rates abroad, China will also be able to continue to lower its own benchmark rates and make its manufacturing base more competitive. Incentives to favor technology development, innovation, the green economy, and import substitutions will be ramped up to follow China’s strategy that was declared at the third plenum, and will support the further competitiveness of Chinese producers.

Nevertheless, if Chinese consumption does not revive, growth will most likely slow further to stay at a level of 2-3% for longer than a decade, the time it will take for excess investments to be depreciated and consumption to become the main driver of the economy.

Despite this, a low economic growth rate does not mean the absence of business opportunities. After all, 2-3% is at the higher end of the expected growth rates of the US or the EU and the sheer size of the Chinese economy will continue to provide considerable opportunities, even with zero growth.

What Comes Next for International Businesses in China?

This new period of economic rebalancing that China is now entering into will bring many opportunities, but it will also come with more risks than foreign investors have been used to.

There are no indications that foreign companies are leaving the market. We do not know of any Swiss firm that has closed its operations in China, though we have heard of a few companies without a local presence that have decided to stop selling in the market.

Still, the opposite approach to the current challenges is more common. Swiss companies that have been doing business in China without a local presence are now setting up shop there in order to better serve their customers and retain their position in the market.

Abandoning the second largest market in the world is not a sensible strategy for most foreign businesses that have had success in China.

Companies that are active in the fastest growing sectors are boosting their investments. For example, at the end of last year Clariant opened a new plant dedicated to anti-flammable materials for EV batteries (ECHEMI, 2023); a Swiss SME producing adhesives specialized for glueing foam is shipping a growing number of containers for automotive and furniture applications from Switzerland to China; Ypsomed is building a 15,000 square metre facility to localize its production of insulin pens (Ypsomed, 2023); and Straumann is investing CHF 170 million in its Shanghai campus and production facility (Straumann Group, 2023).

To mitigate risks, most new investments are made in China with the purpose of serving the local market. For these ‘local for local’ investments to be successful, it is important that they are planned with intensifying competition in mind: high operational efficiency, optimal investment, and running costs need to be built into the concept from the outset and all local available incentives applied for. Reducing financial risks can be done by obtaining loans from local banks that are eager to find good projects to fund and provide attractive interest rates. Continuous sales success will depend on providing best products and developing well-recognized brands for the Chinese market (Section 1.3 of this survey provides detailed insights on these aspects).

To mitigate risks against trade barriers or sanctions, the foreign businesses that export a significant proportion of their product from China are establishing additional operations in other low- or best-cost countries. In doing so, they offer an alternative to their customers who want to de-risk their supply chains. This ‘China +1’ strategy is an effort that requires management resources, additional investments, and a new learning curve. Still, it is considered a worthwhile insurance policy in a climate of uncertain geopolitics.

China’s development plan also offers opportunities to newcomers that can supply new products and technologies. The push for new technology and innovation is generating a strong need for high quality technical products, components and equipment that international companies—particularly Swiss firms are well placed to fulfill. Though China encourages import substitution for mature technologies, the need for rapid development means that advanced and new technologies, highly efficient equipment, or smart innovations are still imported.

China is probably the country that has benefited most from the past 30 years of globalization. Its leaders are very much aware of this fact and they intend to further promote openness and free trade. The recent decision the leadership made to discuss an upgrade of the Sino-Swiss Free Trade Agreement is a good illustration of their willingness to promote China’s international economic integration.

Whether as a local player producing and selling in China or as an international provider importing into the country, the Chinese market keeps on providing important opportunities. Whil the business environment is not easy and will grow ever more competitive, those that enjoy success in China are likely to be extremely competitive worldwide.

References

Bloomberg News. (2023, August 17). China’s abandoned, obsolete electric cars are piling up in cities. Bloomberg News. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2023-china-ev-graveyards/

Business Insider. (2023, April 23). Chinese companies are moving supply chains out of China to manage risks, with India, Malaysia, and Indonesia benefiting. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/asia/south-asia/article/3227015/chinese-companies-are-moving-supply-chains-out-china-manage-risks-india-malaysia-and-indonesia

Capoot, A. (2024, April 10). Apple doubles India iPhone production to $14 billion as it shifts from China. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/10/apple-made-14-billion-worth-of-iphones-in-india-in-shift-from-china.html

Clean Energy Associates. (2024, April 17). PV Supplier market intelligence report (Q2 – 2024). Retrieved from https://www.cea3.com/cea-blog/pv-supplier-market-intelligence-report-q2-2024

Dong, D. (2020, April 29). Houses account for about 70 pct of Chinese households’ assets, putting pressure on consumption stimulation. Global Times. Retrieved from https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1187071.shtml

ECHEMI. (2023, October 23). Clariant opens new production facility in Huizhou Daya Bay. ECHEMI.com. Retrieved from https://www.echemi.com/cms/1434894.html

McKinsey & Company. (2024, June). Economic conditions outlook, June 2024. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/economic-conditions-outlook-2024

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2024, April 24). Industrial capacity utilization rate in the first quarter of 2024. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Retrieved from https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202404/t20240424_1948703.html

Pettis, M. (2022, April 27). The only five paths China’s economy can follow. China Financial Markets. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/china-financial-markets/2022/04/the-only-five-paths-chinas-economy-can-follow?lang=en

Reuters. (2024, April 5). Brazil imports of Chinese electric vehicles surge ahead of new tariff. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/brazil-imports-chinese-electric-vehicles-surge-ahead-new-tariff-2024-04-05/

Rogoff, K. S., & Yang, Y. (2020). Peak China housing (NBER Working Paper No. 27697). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w27697

SolarPower Europe. (2023). Global market outlook for solar power 2023-2027. Retrieved from https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/global-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2023-2027/detail

Strangio, S. (2024, July 2). Indonesia announces hefty tariffs on Chinese-made goods. The Diplomat. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2024/07/indonesia-announces-hefty-tariffs-on-chinese-made-goods/

Straumann Group. (2021, March 26). Media release: Straumann Group expands presence in China building its first manufacturing, education, and innovation center. Retrieved from https://www.straumann-group.com/en/media/details/go-ahead-for-2021-03-26/

Textor, C. (2024, January 2). China: Foreign companies share in import and export from 1986 to 2022. Statistica. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1288326/china-foreign-invested-companies-share-in-total-import-and-export/

Ypsomed. (2023, April 25). Go-ahead for a new Ypsomed production facility in China. Retrieved from https://www.ypsomed.com/en/media/details/go-ahead-for-a-new-ypsomed-production-facility-in-china.html

Zhang, E., & Woo, R. (2022, September 15). Chinese economy’s export pillar shows cracks from global slowdown. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/business/chinas-economy-export-pillar-shows-cracks-global-slowdown-idUSKBN1571BZ

Zhang, L. (2023, July 15). Explainer | A timeline of China’s 32-month Big Tech crackdown that killed the world’s largest IPO and wiped out trillions in value. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3227753/timeline-chinas-32-month-big-tech-crackdown-killed-worlds-largest-ipo-and-wiped-out-trillions-value